Formal Analysis

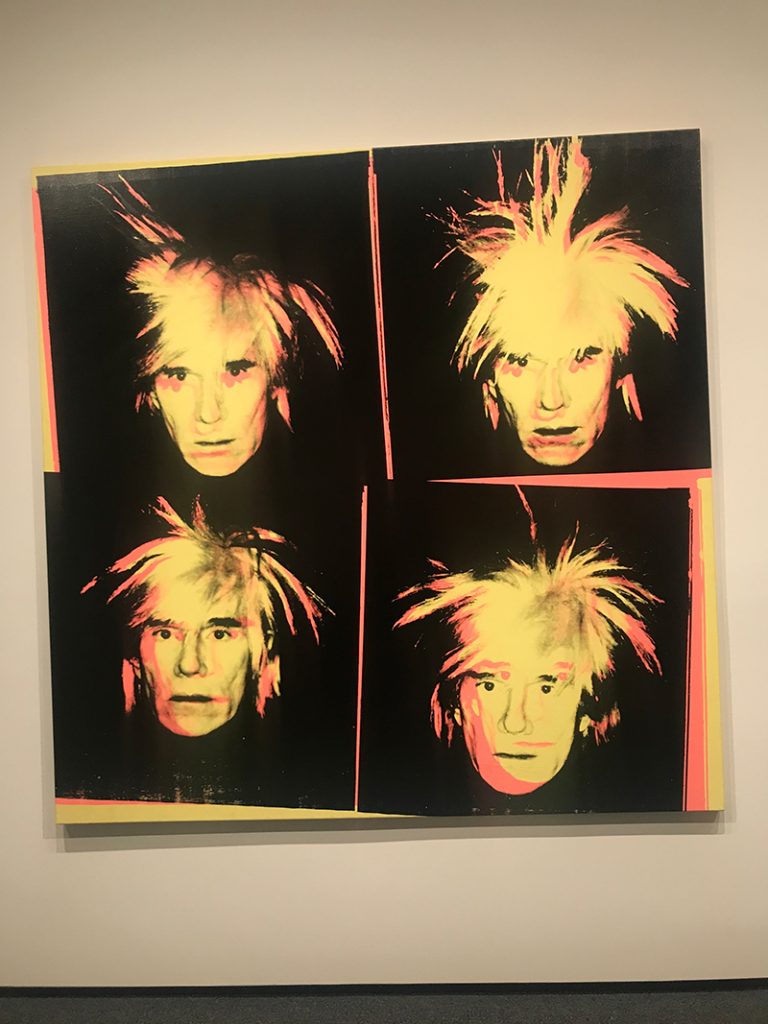

Self-Portrait (1986) by Andy Warhol is approximately 2032 x 2032 mm and was completed through the utilization of acrylic paint and screen print on canvas. The format embodies four squares, two on the top and two on the bottom, Warhol is positioned within each square wearing his iconic white wig. The composition, while balanced is distorted due to the horizontal alignment, but lack of vertical alignment of the two top and bottom squares. In the foreground, Andy Warhol changes facial expression and position within each framed headshot. The focal point resonates on one of the four faces of Warhol, probably the bottom left due to how the square backdrop is positioned. However the eye certainly wanders to each face within the foreground. The movement of the viewer’s eye is achieved through the bold embodiment of color and design.

It is evident that color plays a huge role within this piece. There is strong contrast presented through the solid black background and the limited three color palette of black, pink and yellow. The four square frames encompass the same color sequence and black backdrop, which results in Andy Warhol’s face floating against the black background. The selective use of color is reminiscent of Warhol’s earlier pop pieces, however the transparency and raw portrayal differ from his earlier work. In addition, the repetition of color within each square draws the focus to Warhol’s facial composition and expression.

Self-Portrait (1986) is not a traditional piece and through the screen printing process lights are overexposed and shadows are not as evident. However, it can be assumed that the stark contrast makes the warmer color of pink the shadows and the cooler of yellow the light. The use of lights and shadows only presented upon the four faces of Warhol, further emphasize that the focus is indeed his facial compositions.

Contextual Analysis

Andy Warhol was born in 1928 in Pittsburgh and died in 1987 in New York. Warhol earned his undergraduate degree in pictorial design from Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University).

His work focused on mass media and popular culture. He reflected societal priorities by examining commercialism, mass media and ideological celebrity icons. David Joselit, the Yale professor and art historian who specializes in post-1945 art notes that “in his choice of subject matter, Warhol…recognized that commodities and their human counterparts – celebrities – function as the icons of consumer society,” (Joselit, 2003, p. 77). Within his lifetime, Warhol became a commodity himself, while ironically capturing society’s commodities and their human counterparts.

Warhol believed that everyone would gain 15 minutes of fame and would be briefly graced with the limelight. It is evident within his work and philosophy that Warhol had an obsession with the superficial layers of beauty and fame, and possessed a fascination with societal obsessions. His subjects, including himself were often concealed from imperfection. In his autobiography, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975), there is an emphasis on diminishing personal flaws and imperfections. Throughout his life he suffered from physical ailments, which fostered a lifelong pursuit to mask his perceived flaws. Society destroys icons such as Marilyn Monroe through their obsession and unrealistic expectations, and it’s possible that Warhol’s obsession of beauty and his near death experience are what led to his demise.

A year before his death in 1987, he began creating a final series of self portraits. “Nine months before his death, Warhol created a series of iconic monumental self-portraits featuring his gaunt face, fixed gaze, and a spiky wig, some of the canvases measuring nine feet square,” (Andy Warhol Museum, 2018). His portraiture style and color block format are still utilized, although in a different way than his previous portraits. It is stark in nature with limited color on a displaced inky black backdrop. According to Deputy Chairman of Christie’s Americas and International Co-Head of Post-War and Contemporary Art, Amy Cappellazzo (2011), these self-portraits served as one last look at himself and bravely offered up one of his most open, undisguised and unmanipulated self-depictions. However, there is still a sense of hidden identity and sense of self. Warhol created a sense of masquerade by putting on his famous fright wig. Even in his most intimate portrayal, his sense of being and identity were in-genuine and hidden behind costumes, make-up, plastic surgery and his fright wig.

Warhol started creating self portraits in 1964 and continued to do so throughout his career. “Art historian Carter Ratcliff has warned against a solely superficial reading of Warhol’s portraits, arguing that ‘as blank and anesthetized as his surfaces sometimes are, they hide depths of a traumatized self or a deep sense of the random and depersonalized tragedy of the modern world,’” (Kear, 2015). Warhol’s trauma from his near death experience in 1968 is exhibited in his work and how he depicts himself in self portraits. Warhol was known for depicting celebrities as societal icons, however as described by Amy Cappellazzo, Deputy Chairman of Christie’s Americas and International Co-Head of Post-War & Contemporary Art (2011), by the time he exhibited the 1986 series of Self-Portrait works, Warhol had become a celebrity in his own right and a societal icon.

Andy Warhol and His Sense of Identity

Andy Warhol’s final self portrait series reveal his evolution of identity and self. The 1986 Self-Portrait investigated Warhol’s beauty fixation and how it affected his portrayed identity and connection to the world. His work examined societal perceptions that revolve around commercialism, mass media and ideological celebrity icons. While presenting a reflection on societal priorities and the fascination of celebrities, Warhol became a celebrity in his own right. However, as a form of protection, he established a public persona that distanced himself from the world and his identity. Beyond commercialism, Warhol’s identity and self image were largely based on his life-long insecurities, health issues and struggles with his outward appearance. In accordance with fame and outward appearances, Warhol’s identity was forever altered by Valerie Solanas’ failed assassination attempt in 1968. The superficial layers of his Self-Portrait (1986) encompass bold design and recognizable qualities of pop art, however beyond the surface Warhol’s struggle with identity and personal autonomy are revealed.

Warhol was known for depicting celebrities as societal icons and had become a celebrity in his own right. He achieved celebrity status through a consistent brand identity within his art practice and personal autonomy, not unlike the commodifications he depicted. According to Kelly Sidley’s dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the Institute of Fine Arts of NYU (2006), “Warhol’s suggestion that he was more like an object than a subject, more like one of his silkscreened portraits than the actual people portrayed on the canvases, helps to explain how he crafted the public image that came to define him,” (p. 75). Warhol’s demeanor and public identity began to form a connection between himself and his work. This connection further modified his identity and solidified the fact that everything the world knew about Warhol was what he presented to the world. By 1965, Warhol had established his public persona “defined by a unique physical appearance and an enigmatic personality, his intricately constructed persona helped to make him the most recognizable artist of the postwar era,” (Sidley, 2006, p. 11).

Warhol concealed identity and denied the world of his sense of self by utilizing his public image as a readymade, as opposed to revealing his humanity and vulnerability. Cécile Whiting, a Professor of Art History at the University of California (1987) believes that through the utilization of the public image, “Warhol denied the existence of [the] private self…[he provided] the negation of the private individual self in both Warhol’s portraits and his own public persona,” (p. 58). By further extending his artistic brand through his public image, Warhol implemented a “masterful plan for creating a public persona [that] prevented him from revealing information on his background and personal life…By never satisfying the public’s desire for concrete information, the media kept asking about the ‘real’ Warhol,’” (Sidley, 2006, p. 74). Through his public persona and consistent brand, Warhol was able to control how the world perceived him. He would rather have the world perceive him and his work as shallow and robotic than reveal the pure depths of his identity. Warhol was known for stating “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am.” His philosophy demonstrates that Warhol wanted the world to analyze his work, pop culture commodities and himself purely on a superficial level. This leads to “the surface treatment of his self-portraits [and] emphasized his physicality while downplaying any emotional or psychological content,” (Sidley, 2006, p. 5). By diverting the world’s attention against his true autonomy, his work and identity would only be read as a superficial entity, thus concealing his identity and protecting him from the world.

Beyond himself, his subjects were the pinnacle of beauty, fame and fortune. However, Warhol, an icon and star in his own right, was never depicted in that light. American philosopher, art and cultural critic, David Carrier (1998) believes “to the extent that what for him defined beauty was glamour and stardom, certainly he had every reason to think himself beautiful. And yet he did not take this outside view on himself. So generous at seeing others as beautiful, Warhol found himself homely, ugly, and unlovable. That was his blind spot,” (p. 38). Warhol’s detached public persona and fascination with the physicality of beauty could be attributed to his lifelong insecurities and health issues. “Throughout his life, Warhol fixated on his physical imperfections. As a child, Sydenham chorea (St. Vitus dance) occasionally kept him bedridden, and he had pigment issues that caused discoloration of his skin, leading to the nicknames ‘Spot’ and ‘Andy the Red-nosed Warhola,’” (Andy Warhol Museum, 2018). Due to his physical aliments including skin discoloration, premature baldness and 1968 gunshot wounds – Warhol fostered a lifelong interest in masking his perceived physical flaws.

Beyond cultivating a public persona, Warhol drastically altered his appearance in order to conceal his insecurities and discomfort. According to Kelly Sidley’s 2006 Ph.D dissertation, photographs from the first half of the 1960s document a deliberate shift in Warhol’s appearance. Warhol’s outward appearance progressed from wearing hats into wearing hair pieces and wigs. In addition, he altered his appearance through clothing, sun glasses, plastic surgery, dermatology treatments and make up. “During the sixties many of Warhol’s physical transformations, most of which amount to costume and accessory choices, go beyond wanting a natural look. Instead, the artist opted for a more eccentric, grungy style that, perhaps in Warhol’s own mind, helped to detract from his physical insecurities,” (Sidley, 2006, p. 65). His fixation on beauty and altered appearance provided a barrier that allowed him to investigate the world and cast attention away from himself. According to American philosopher, David Carrier, Warhol’s deeply felt conviction that he was physically undesirable enabled him to refocus his reflection on the world and treat his work as a mirror to society. Therefore he externalized “a way of viewing the world, expressing the interior of a cultural period,” (Carrier, 1998, p. 39), but failing to reveal his true identity.

In accordance to his detached persona, physical ailments and insecurities, Warhol’s identity was forever altered by the failed assassination attempt by Valerie Solanas in 1968. Radical feminist, Valerie Solanas attempted to murder Warhol by shooting him. She had developed resentment toward him, due to his disinterest in producing her play, and losing her script. After the assassination attempt, Warhol stated: “‘I realized that it was just timing that nothing terrible had ever happened to any of us before now. Crazy people had always fascinated me because they were so creative. They were incapable of doing things normally. Usually they would never hurt anybody, they were just disturbed themselves; but how would I ever know again which was which,’” (Danto, 2009, p. 101). Warhol’s trauma from his near death experience in 1968 is exhibited in his work and how he depicts himself in self-portraits. While his later work is reminiscent of earlier pop elements, there were darker depictions of mortality and hidden depths of identity. “It is often said that Valerie Solanas’ attack was a dividing line in Andy Warhols life, and that he became a different artist in consequence of the violence, which left him momentarily dead and permanently traumatized,” (Danto, 2009, p. 120).

Toward the end of his life and career, Andy Warhol’s art dealer, Anthony D’Offary wanted Warhol’s new self-portraits to be reminiscent of his earlier work before the attack. According to Deputy Chairman of Christie’s Americas and International Co-Head of Post-War and Contemporary Art, Amy Cappellazzo, Warhol’s life and art process drastically changed after getting shot by Valerie Solanas. Since then Warhol questioned his own mortality and D’Offary wanted Warhol to revert back to his earlier art process. Even though his identity remains concealed, there is more vulnerability and sense of self in his later work. The final self-portrait series were a collaborative effort between Warhol and D’Offay. The photographs that D’Offray opposed were utilized for Warhol’s 1986 Self-Portrait displayed at the National Gallery of Art. Anthony D’ Offay described the images utilized in this piece as having a demonic aspect and the facial qualities of a death mask. In these self-portraits “the screen is similar in screen and composition, but the wig’s strands stand up on end. Andy has a much more gaunt look on his face…[in the] death mask series, haunting, house of horrors as D’Offay refers to it, look on his face,” (Cappellazzo, Christie’s, 2011). Comparative to his earlier self-portraits, there is a stronger sense of self and certainty in his last self-portrait series even if the facial qualities of a death mask are exhibited.

Throughout Warhol’s career and evolution of self portraiture, identity played a prominent role in his depictions. Warhol was fixated on beauty and the different facets of everyday life. He examined mass media icons, commercialism and human commodities. Through his examination, he cultivated a prominent public persona that served as a barrier to the public. His evasive public persona, utilization of readymade images and masked insecurities allowed him to conceal his identity within his work. Warhol became a human commodity, not unlike the ones he depicted and proposed that only superficial entity be analyzed. Furthermore, his identity was forever altered by the trauma inflicted on him by Valerie Solanas in 1968. However, at the end of his career, The Self-Portrait (1986) series served as “one of his most open, undisguised and unmanipulated self-depictions,” (Cappellazzo, Christie’s, 2011). Even though there is still a hidden sense of identity and self through masquerade, it is one of his most intimate portrayals of self. It was Andy’s “Last glance at himself,” and during the exhibit in which it was displayed, there was instant sense of celebrity and success. Andy was seen as an icon and celebrity in his own right.

Bibliography

The Andy Warhol Museum. 2018. “Andy Warhol’s Life.” https://www.warhol.org/ andy-warhols-life/

Cappellazzo, Amy. 2011. “Gallery Talk: Andy Warhol’s Self-Portrait, 1986.” Christie’s. Video, 7:06. https://www.christies.com/features/gallery-talk-warhol-self-portrait-1986-1443-3.aspx

Carrier, David. “ANDY WARHOL AND CINDY SHERMAN: THE SELF-PORTRAIT IN THE AGE OF MECHANICAL REPRODUCTION.” Source: Notes in the History of Art18, no. 1 (n.d.): 36–40.

Danto, Arthur C. Andy Warhol. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Kear, Jo. “Andy Warhol Self Portrait 1986.” Tate, October, 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/warhol-self-portrait-t07146

Sidley, Kelly. “Beyond Self -Portraiture: The Fabrication of Andy Warhol, 1960–1968”. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, n.d.

Warhol, Andy. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again. New York: Harcourt INC, 1975.

Whiting, Cécile. “Andy Warhol, the Public Star and the Private Self.” Oxford Art

Journal 10, no. 2 (n.d.): 58–75.